Ireland, Island of Writers: What’s behind Ireland’s literary spark

Ireland has long held a distinguished place on the world’s literary stage. From the epic tales of early mythology to the modern-day Booker Prize winners, our small island on the edge of Europe has produced a remarkable wealth of storytellers across genres and mediums who have helped to shape, and sometimes shake, the literary world.

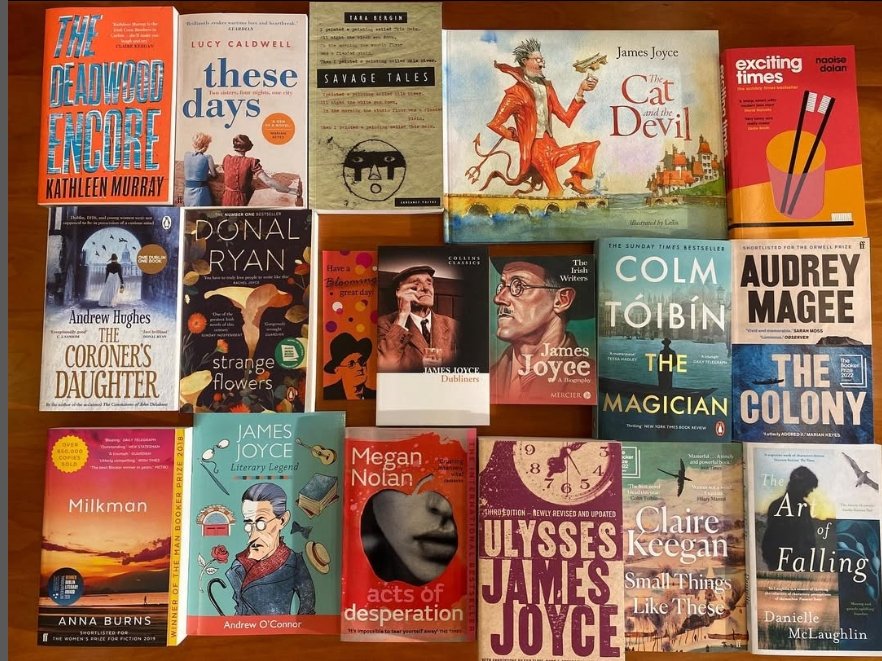

For a nation of just five million people, our contribution to global literature is disproportionately large, and consistently influential and inspiring, from James Joyce to W.B. Yeats, and Sally Rooney to Colm Toibín, and many more. The question, often asked with genuine curiosity, is: why?

Why does Ireland have this reputation for such a rich literary culture?

The answer lies in a combination of history, culture, infrastructure, and an enduring national respect for the written and spoken word. Ireland’s literary heritage is undeniably rich, and our roots in writing run incredibly deep.

This is the land where bards once held status just below kings, and the land of four Nobel Prizes in Literature, won by W.B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Samuel Beckett and Seamus Heaney. Each is not just a great Irish writer, but a giant in the literary world.

And yet, Ireland’s literary story is not stuck in the past. In recent years, Irish writers have become staples on international shortlists – from Claire Keegan’s emotionally searing novellas to Paul Lynch’s 2023 Booker Prize win for his novel Prophet Song. Sally Rooney’s brand of cerebral millennial melancholy has found a global fanbase, while younger voices like Naoise Dolan and Colin Walsh continue to make waves far beyond Irish shores.

When Paul Lynch won the Booker Prize in 2023, he was the sixth Irish author to win the prestigious award and one of four Irish authors on that year’s longlist of 13.

When asked why the Irish representation was so strong afterwards, he simply said: “It’s a great place for writers.”

Storytelling, an Irish pastime

Ireland’s ongoing literary success is no doubt rooted in our historical relationship with language and storytelling. Storytelling is in our bones, and has long been stitched into the Irish national psyche.

The oral tradition has always been central to Irish life, with stories passed down through generations as a way of preserving identity, history and values.

This tradition, once carried on by seanchaís [traditional storytellers], is still alive and kicking in everyday life and filters down into everyday interactions and even our patterns of speech.

In Irish, we say ‘Cad é an scéal?’ as a means of saying how are you, but it directly translates as ‘What is the story?’. It’s common in Ireland to greet a friend or acquaintance with the phrase ‘C’mere ‘til I tell you’ to preface your latest news. Storytelling is built in to the Irish way of communicating, and it’s both sport and an art form.

The influence of that ingrained urge to share stories remains. Today, whether in literature, theatre, or spoken word, Ireland continues to value the power of narrative and the skill of the storyteller.

“There is a love of language and an innate creativity in the use of language that I think comes through in everything from Yeats and Joyce, up through Anne Enright and Sally Rooney.”

Ireland’s complex history makes for good fodder

Irish authors have rarely found themselves wanting for inspiration. Ireland’s complicated and layered political and social history has provided fertile ground for literary exploration for decades.

Centuries of colonisation, emigration, rebellion, famine, partition, and political upheaval have given generations of writers something to chew on. And chew they do, most often with sharp wit, a critical eye, and no fear of uncomfortable truths.

Contemporary Irish authors

“Irish literature resonates with Africans a lot. It articulates a shared tragedy but does so with so much humour, which is very, very African,” says Joke Silva, Nigerian actress and director.

Themes of identity, belonging, displacement, and resilience are common features of Irish writing. Contemporary Irish literature still draws on these themes, while also exploring issues such as gender, sexuality, class, and migration in increasingly diverse and innovative ways.

“Irish writing has a global resonance because of its daring, experimental spirit and its all-embracing open-mindedness. To be local, is to be global.”

Language matters

Cultural suppression, and particularly the erosion of the Irish language, historically meant that writing became a form of cultural survival, a way to reclaim our identity and voice.

When Irish people were forced to adopt English, we didn’t just use the language, we reshaped and stretched it, bringing to it the cadence, rhythm, and wit of the Irish language, along with a sense of defiance and resistance.

Irish writing was then, and continues to be, deeply personal and often fiercely political.

“Irish literature resonates globally because it articulates the universal struggle of forging an identity in the face of cultural and linguistic constraints, and this is a common issue across so many different regions of the world."

Building a strong creative landscape

While history and tradition have laid the foundations, talent needs more than inspiration to survive. Brilliant writers need a creative ecosystem and cultural infrastructure that supports them not just in spirit, but in livelihood too.

Part of the Irish success comes down to a deep, stubborn belief in the value of writing. Ireland takes its literature seriously, and not in a lofty and exclusive way, but in a deeply democratic way. There’s a kind of national pride in “our writers,” and that pride translates into support, both cultural and practical.

Fostering literary talent in Ireland is a priority, and we have created a national infrastructure to support writers. Organisations like the Arts Council of Ireland provide grants and bursaries to emerging and established writers, meaning that people can afford the time to write.

Then there are institutions like Literature Ireland, which has funded the translation of over 2,500 works of Irish literature into 58 languages around the world, ensuring that Irish voices reach readers across the globe.

Poetry Ireland champions poetry through readings, education and mentorship programmes, while Fighting Words, co-founded by author Roddy Doyle, plays a vital role in nurturing the next generation, offering free creative writing programmes for children and young people across the country.

Nurturing new voices and talents

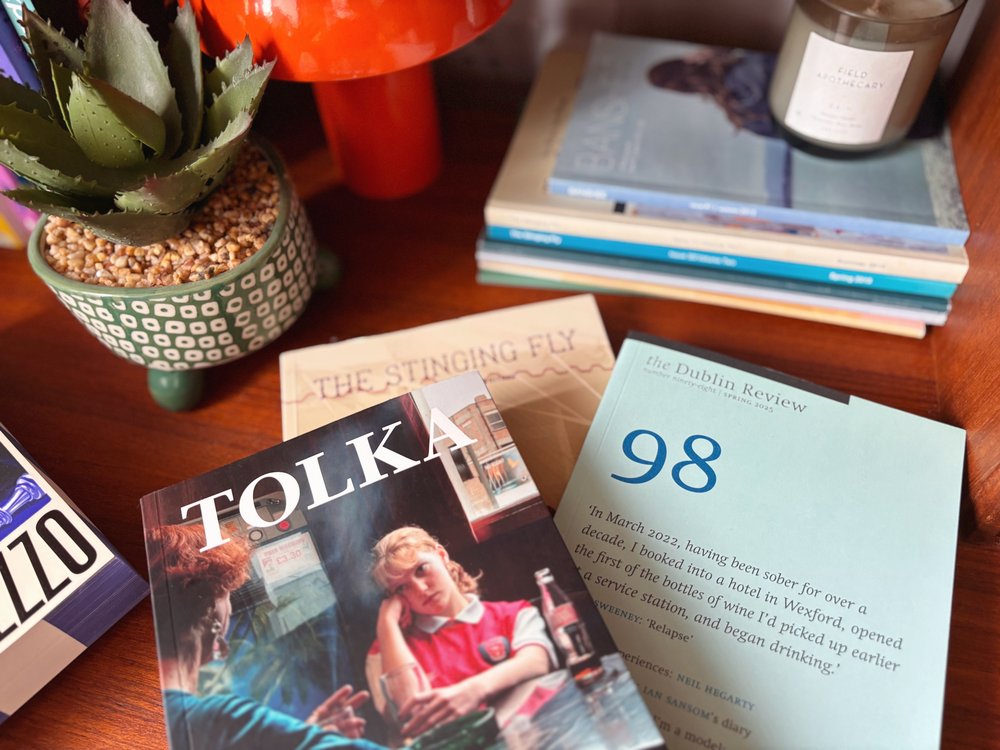

There is a healthy ecosystem of literary journals that feature known names alongside newcomers, offering a space where new voices can be nurtured. The Arts Council funds literary magazines like The Dublin Review, Banshee, Tolka and The Stinging Fly – the latter of which first published Sally Rooney in 2010, and has been profiled by the New York Times.

“It [The Stinging Fly] has become prime poaching ground for editors in other countries hungry for Irish talent,” Max Ufberg wrote in 2023.

The effect of this nationally backed support for literary journals is a publishing landscape that can afford to be less concerned about profitability and more concerned with offering proving grounds and momentum for new talents, as well as keeping the national literary conversation fresh and evolving.

Year round festivities for literature

Ireland also places a heavy priority on our literary festivals – of which there are quite a few.

The International Literature Festival Dublin, Listowel Writers’ Week, Cúirt International Festival of Literature, West Cork Literary Festival, and Aspects Festival are just some of these festivals that celebrate Irish writing and create inclusive spaces that bring together writers and readers in real conversation.

They intentionally look to demystify the literary world, and make it accessible, visible and relevant for a general audience.

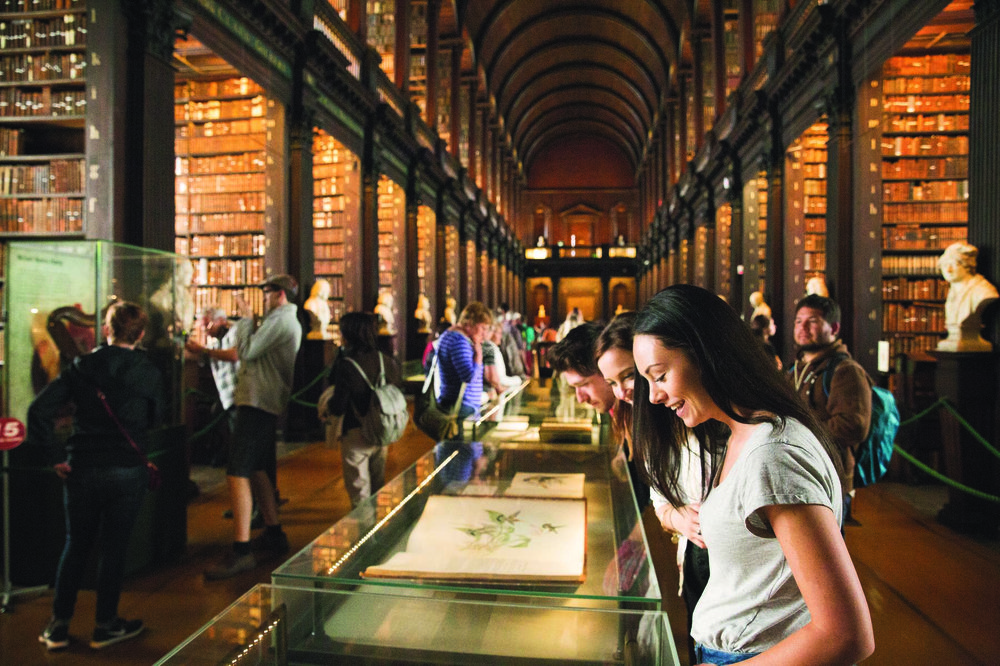

Libraries: a quiet engine for literary accessibility

In a similar accessibility vein, it’s worth noting Irish libraries are one of the quiet engines behind our strong literary culture. Publicly funded and deeply valued, they offer not just free access to books but community spaces which host readings, book clubs, writing workshops and children’s story hours, making them vital entry points into the world of literature.

Against a backdrop in many locations across the world where libraries are being closed systematically, largely for budgetary reasons, Ireland has committed to treble the number of libraries in Ireland with extended opening hours 365 days per year and to develop every library in the country into a multi-purpose education and social space under the National Public Library Strategy.

Education as a powerful force

Education is also a crucial factor. Literature remains a central part of the Irish school curriculum, with students engaging deeply with poetry, drama, fiction, and critical thinking from an early age.

Irish teenagers emerge from their final school exams, the Leaving Certificate, with a working knowledge of dramatic monologues, modernist fiction, lyrical poetry and everything in between, spending their school years reading not only global classics but also the works of homegrown writers.

This educational emphasis helps to cultivate not only future writers, but informed and passionate readers. Irish universities continue this tradition with strong programmes in English literature and creative writing, often led by acclaimed writers and scholars.

An upward trajectory

Irish literature has never stood still, growing from oral tradition and epic poetry, and the experimental modernism of Joyce to the razor-sharp prose of today’s rising stars.

Contemporary Irish writers are winning major international prizes, redefining genres and telling stories that feel urgent, intimate, and entirely their own.

This literary strength isn’t accidental, or just luck. It’s the result of a culture that values language, a society that invests in writers, and a readership that still believes in the power of a good story, well told.

Ireland may be small, but our writers have made an outsized mark on the world’s bookshelves. Our literary voice continues to resonate far beyond our shores, and it’s a voice that shows no signs of quietening down.