Monumental design: The Irish architects behind the Grand Egyptian Museum

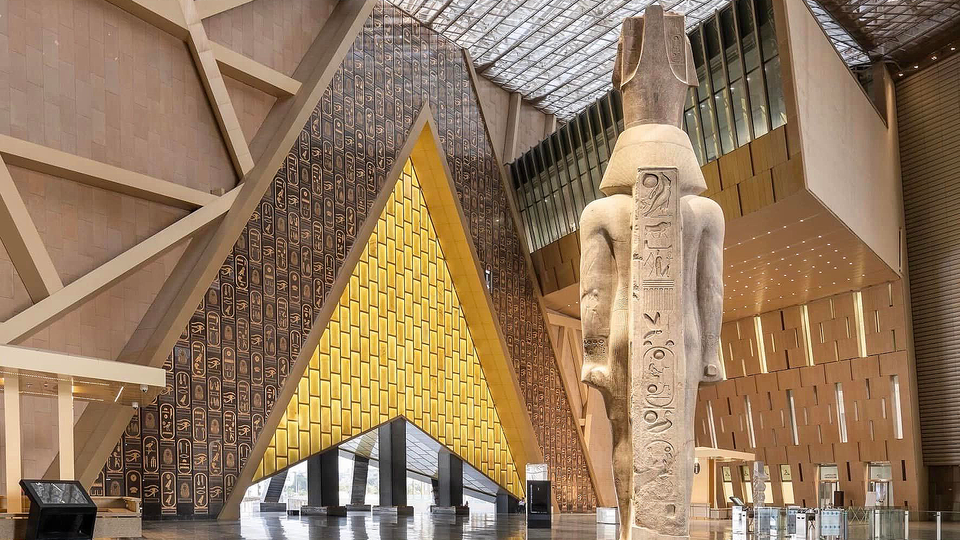

Few cultural architectural projects match the scale of the Grand Egyptian Museum, which is the largest museum in the world dedicated to a single culture.

Set against the backdrop of the Giza pyramids, it spans half a million square metres and will house the world’s most extensive collection of Egyptian antiquities across 100,000 artefacts.

Two decades in the making, it represents a rare blend of engineering ambition and cultural preservation, a global collaboration involving an Irish architectural studio.

Heneghan Peng Architects, led by Irish architect Róisín Heneghan and Taiwanese-American Shih-Fu Peng, won the international competition for the museum in 2003, emerging from more than 1,500 entries.

“Design competition is a fairly open way for architects to get work,” Heneghan explains. “It’s based on the design that you submit, and not based on previous experience.”

Sensitivity to place in design

For the Dublin-based practice, the project began with deep sensitivity to place. “The site is very, very close to the pyramids, and for us that was what was most important,” she says.

“We felt that this was the first time in living memory where those objects that are the archetypes of this civilisation, that they can be seen in the same space as the pyramids.”

That relationship to the desert and the Nile became the project’s guiding idea. The museum is located on a desert plateau at the edge of Cairo, and one of Heneghan Peng’s central designs was to extend the museum outwards towards the pyramids along a precise visual axis, ensuring the pyramids are a constant backdrop when looking out from the museum.

We looked to create a new face to that desert plateau, staying below the level of the Nile and creating a new line that unfolds to take in the view of the three pyramids.

“It just makes sense if you consider the museum in relation to the pyramids, because it’s entirely structured around that view, ” she says.

The visitor's journey

Inside, the visitor’s journey mirrors the architecture’s unfolding logic. A monumental staircase runs through the building’s centre, ascending through its six storeys.

Visitors move from Egypt’s earliest settlements to its Coptic era, ending in the Tutankhamen Gallery where over 5,000 artefacts are displayed together for the first time.

A journey through time

The journey through the museum is a carefully plotted journey through time, punctuated by statues and architectural fragments displayed along the landings.

“What we did was we put the permanent exhibition galleries up at the top, because it's from there you can see to the pyramids. It's very much about that relationship to the pyramids and trying to point to the biggest artefact, the pyramids, which are outside of the museum,” explains Heneghan.

“To be able to stand there in the middle of a very busy urban environment, which Cairo is, and have this view, you don’t see a whole lot of stuff between you and the pyramids. To be able to manage that, bringing that collection back to that space, this collection of pyramids and sphinx, was quite special.”

Environmental considerations

The building’s environmental design also required innovation at scale. “It’s a very, very large building,” Heneghan explains. “Because of the collection, there are elements in it that are very sensitive. So any human remains, papyrus, they are incredibly sensitive. There’s huge amounts of others that are stone and that is a lot more variable.”

The team designed for long-term resilience. “The building is very, very heavy, so that it slowly acclimatises. It’s quite resilient in that way. The entrance is actually a shaded space. It’s not actually an interior space, so we don’t need to condition it, but because it’s shaded, we can control the temperature. And gradually the environmental control increases throughout the museum.”

Serving Cairo's residents

This careful zoning ensured the museum would be both sustainable and operable in Egypt’s demanding climate. But, Heneghan also wanted the site to serve Cairo’s residents.

“Cairo has very little open space,” she says. “So what we also wanted to do was develop the gardens to the front of the museum, so that it might also become a resource for this west side of Cairo."

We were trying to think about it outside of just tourism, thinking about how might it support the Egyptian community as well. There are a lot of learning and educational spaces too.

Though the Grand Egyptian Museum was the firm’s first major museum project, it set the course for many more. “We have since done the National Gallery of Ireland, their historic wings refurbishment,” she says. “And we’ve done a museum in Palestine in Birzeit University in the West Bank, and a small museum in Germany as well.”

Combining technical design with storytelling

For Heneghan, museum design combines technical design and an emotive storytelling element. “You’re always thinking about how people are going to experience the place. There’s always that discussion around creating perfect spaces for the art, and then also, how do people see it? Do they feel it’s in a context or is it an object on its own?

And then there's the other side, making the insular spaces, the learning spaces. You’re asking: ‘How do people engage?’, ‘How do you learn from their art?’, ‘How do you make space for people to think about their own work?’ You’re looking at how people can not just view it, but can become an active participant,” she explains.

A little known Irish connection

While this was Heneghan Peng’s first architectural project in Egypt, there is a little known Irish connection in the design beyond the architect's County Cork roots.

“While we were working on the project, we worked with a mathematician on the structure. He was always kind of doing all these crazy calculations,” she laughs. “One of them was that if you took the geometry, if you expanded the geometry of the line [of the view from the building], it connected to Dublin. That was Francis’ theory!”

Standing before the pyramids

As the Grand Egyptian Museum prepares to open, her hopes are focused on what visitors will feel when they stand before the pyramids once more.

“Seeing those pieces beside the pyramids is very, very different to seeing them in a building in the centre of Cairo, where you’re surrounded by the city. Here, you’re so close to that site [the pyramids], that seeing the collection here resonates differently. I’m hoping that does resonate with people.”

Find out more about Heneghan Peng and their architectural projects across the globe on their website, hparc.com.

All images courtesy of the Grand Egyptian Museum and Heneghan Peng Architects.