The Irish Palatine Story

Our shared journey

The most impactful and sustained historical link between Ireland, Rhineland-Palatinate and neighbouring states are the so-called Irish Palatines.

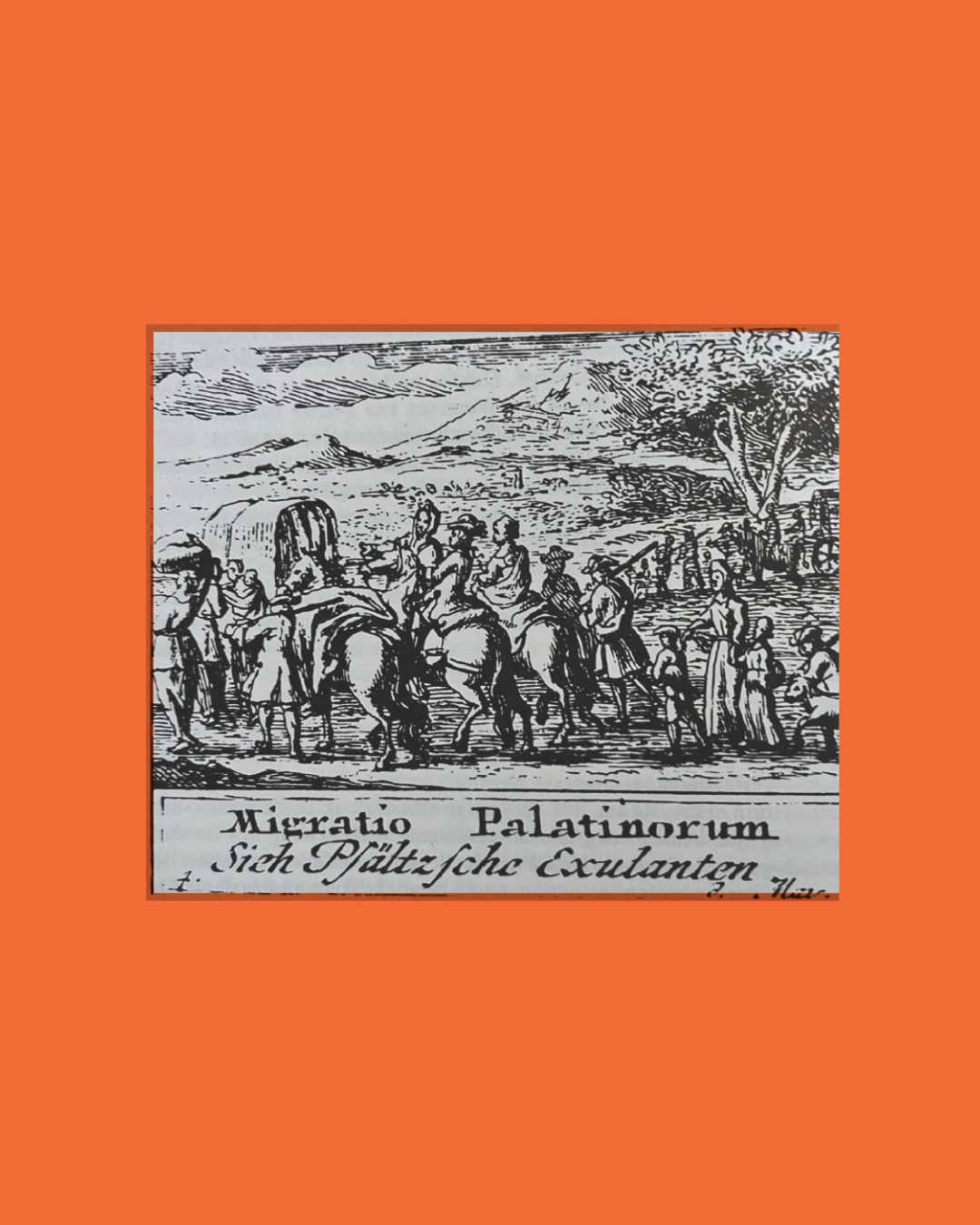

This was a loosely-associated group of approximately 3,000 migrants from modern-day Rhineland-Palatinate, Hesse, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, who left in 1709 due to the impact of the War of the Spanish Succession and famine and the promise of refuge and a better life abroad.

Irish Palatine settlements were later established across Ireland, with particular concentrations in Counties Limerick, Kerry, Tipperary and Wexford.

Bearing surnames such as Baker, Cave, Crowe, Heck, Shier, Switzer, Teskey, Ruttle, Wolf and Young, their descendants have long been fully integrated and continue to make significant contributions to Irish life across a range of fields.

The Irish Palatine Project raises further awareness of this tangible, people-to-people connection which has enjoyed continued relevance from the 1700s to the present.

Thirty Years' War

A particularly sustained and consequential European conflict was the Thirty Years’ War, which was sparked in 1618 when a Catholic, Emperor Ferdinand II, was replaced as King of Bohemia by a Protestant, Frederick V of the Palatinate.

What followed was three decades of war, featuring not only internal conflict between Catholic and Protestant territories in the Holy Roman Empire but also a wider, hegemonic struggle for European dominance.

Given its Elector was centrally involved from the outset and its proximity to France, it is unsurprising that the Palatinate was deeply affected by this conflict. The electorate was conquered by a Spanish-Bavarian coalition in 1623, with the title of Elector Palatine reassigned to Maximilian I of Bavaria thereafter.

Thirty Years' War

A particularly sustained and consequential European conflict was the Thirty Years’ War, which was sparked in 1618 when a Catholic, Emperor Ferdinand II, was replaced as King of Bohemia by a Protestant, Frederick V of the Palatinate.

What followed was three decades of war, featuring not only internal conflict between Catholic and Protestant territories in the Holy Roman Empire but also a wider, hegemonic struggle for European dominance.

Given its Elector was centrally involved from the outset and its proximity to France, it is unsurprising that the Palatinate was deeply affected by this conflict. The electorate was conquered by a Spanish-Bavarian coalition in 1623, with the title of Elector Palatine reassigned to Maximilian I of Bavaria thereafter.

The instalment of this Catholic ruler brought about great changes for the Palatinate’s Protestant population, particularly when combined that same year with Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand II’s Edict of Restitution. This directive forced Protestant rulers across the empire to restore over 500 Catholic properties of various sizes to the church.

An era of relative religious pluralism and coexistence followed the signing of the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, which entrenched theological divisions between Catholicism and the various Protestant denominations. Most importantly, however, the Treaty decentralised German power structures until unification in 1871.

Ireland was Britain’s first colony and had been under varying degrees of British rule since 1169. Many of the earlier settlers from Britain integrated into Irish society, adopting Irish language and customs.

This created considerable tension with later settlers, particularly after the Protestant Reformation in the 16th and 17th centuries, when the English Crown re-assigned confiscated Catholic lands to Protestants from England and Scotland as part of the Plantations.

These tensions peaked during the 1641 Rebellion, when a Catholic coalition known as the Confederacy forcefully seized control of Ireland, with thousands of Protestant casualties. Oliver Cromwell reconquered Ireland in his capacity as Lord Protector, suppressing all opposition by 1653.

This period of conflict, collectively referred to as the Irish Confederate Wars, had a devastating impact on Ireland’s Catholic population, with over half of the island’s 1.5 million inhabitants either dead or displaced.

This demographic collapse further reduced the percentage of Catholic-owned land in Ireland, which dropped from 59% in 1641 to 22% in 1688.

By the time the new Kingdom of Great Britain was formed in 1707, Catholic opposition in Ireland was firmly suppressed and a period of relative peace followed.

This pattern was to continue, largely uninterrupted, until the late 18th century when the republican ideals of the French Revolution inspired a new generation of Protestants and Catholics to strive for Irish independence.

The fortunes of late 17th century Palatinate, Hesse and Baden were decisively shaped by the foreign policy objectives of the then dominant political figure in Europe, King Louis XIV of France. Reigning from 1661 to 1715, his approach towards German lands was one of expansion, with the ultimate aim of making the Rhine River France’s new eastern border. This mission began in earnest in 1670, when he occupied Lorraine. This advance reached the towns and cities along the Rhine by 1689 with devastating effect, resulting in the destruction of Heidelberg, Mannheim, Oppenheim, Worms, Speyer and Bingen between March and June of that year.

Louis’ expansionist agenda was opposed by King William III of England, who led an anti-French coalition, which became known as the Grand Alliance. The Grand Alliance fought a number of major battles against French forces, including Blenheim (1704), Ramillies (1706), Oudenarde (1708) and Malplaquet (1709), but neither side gained a decisive upper hand. Against this backdrop, the winter of 1708/9 is remembered as the Great Frost by virtue of being the coldest over the last 500 years of European history. This had a particularly pronounced impact on Palatinate, Hesse and Baden, where crop failures and famine ensued.

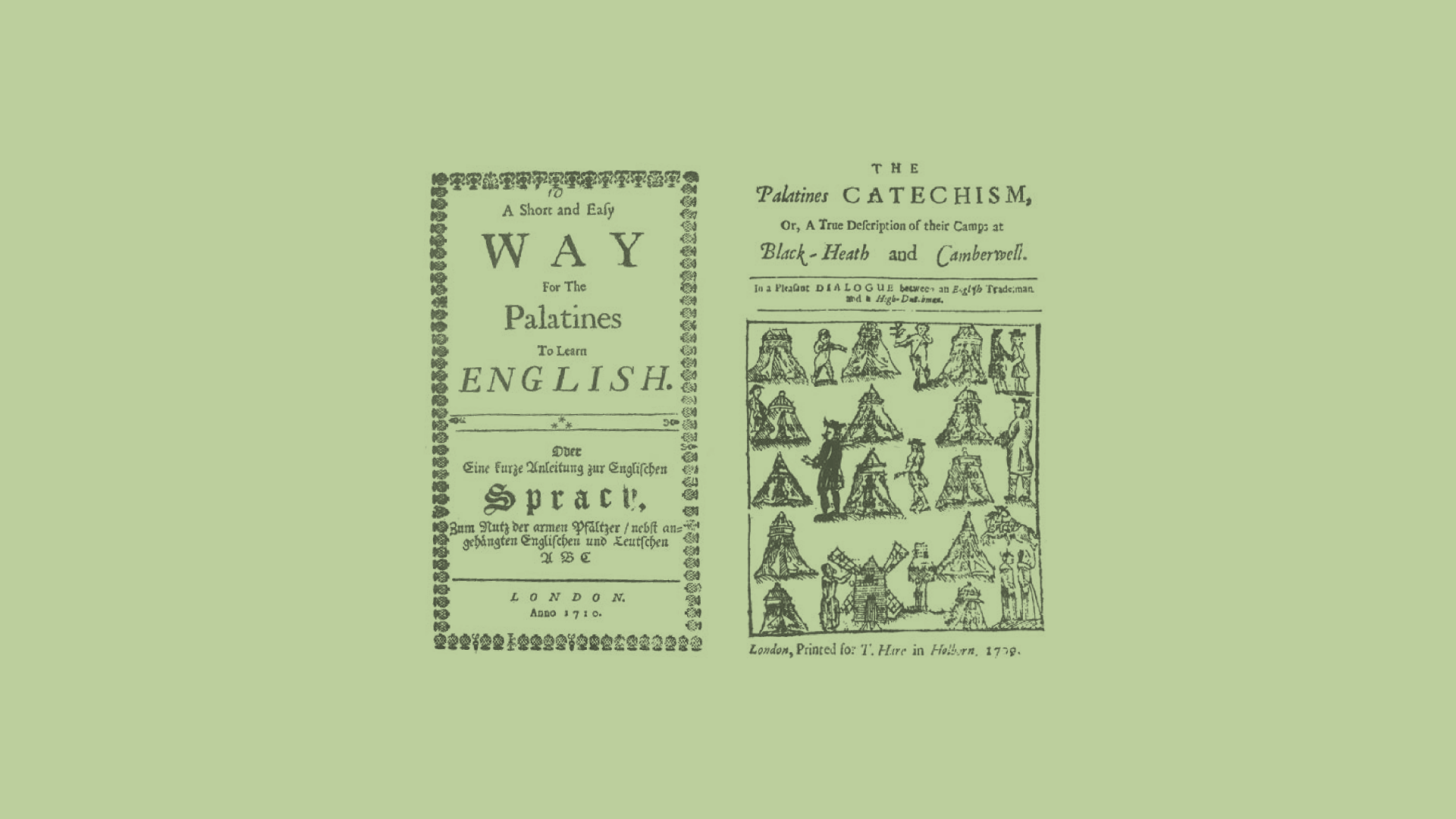

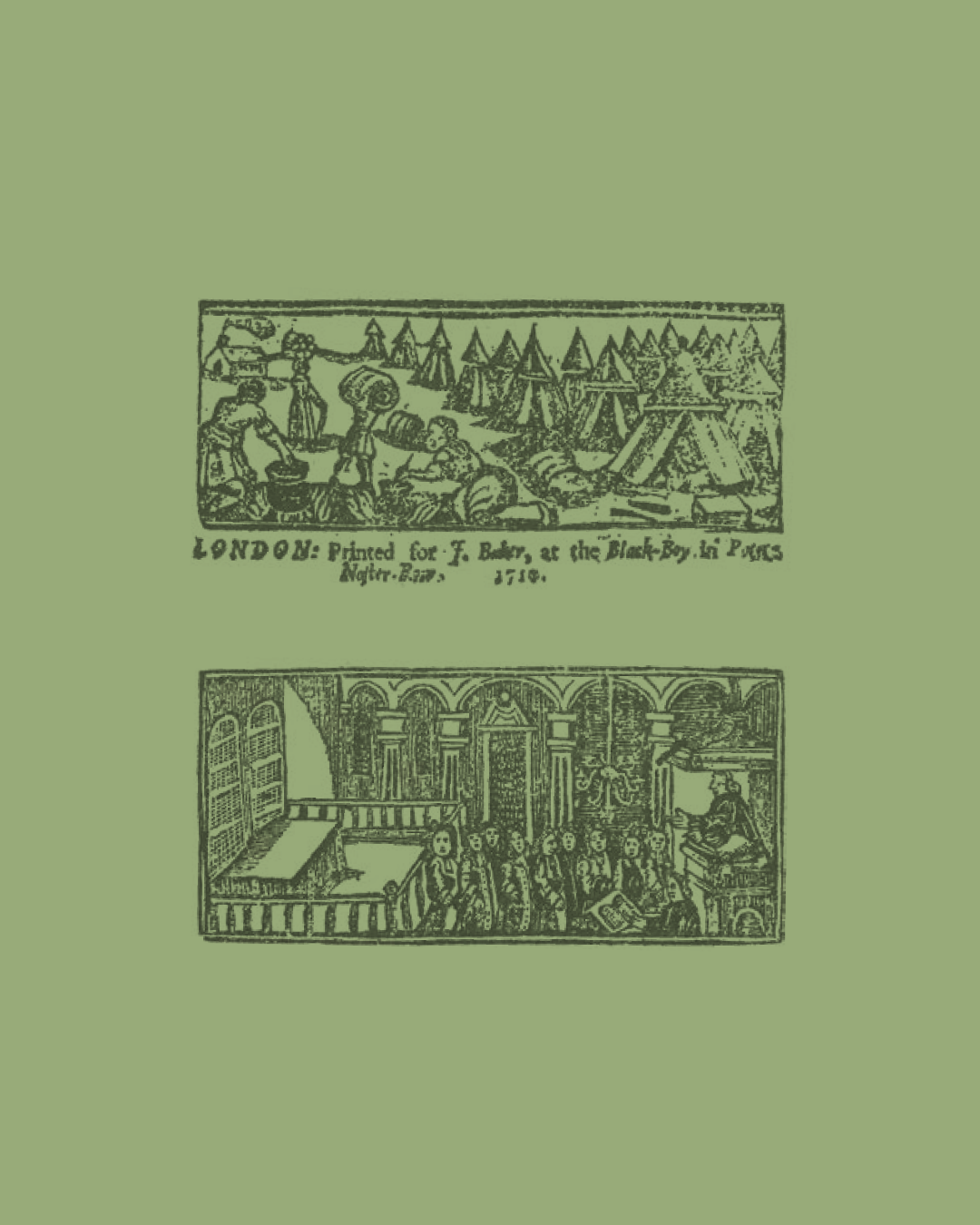

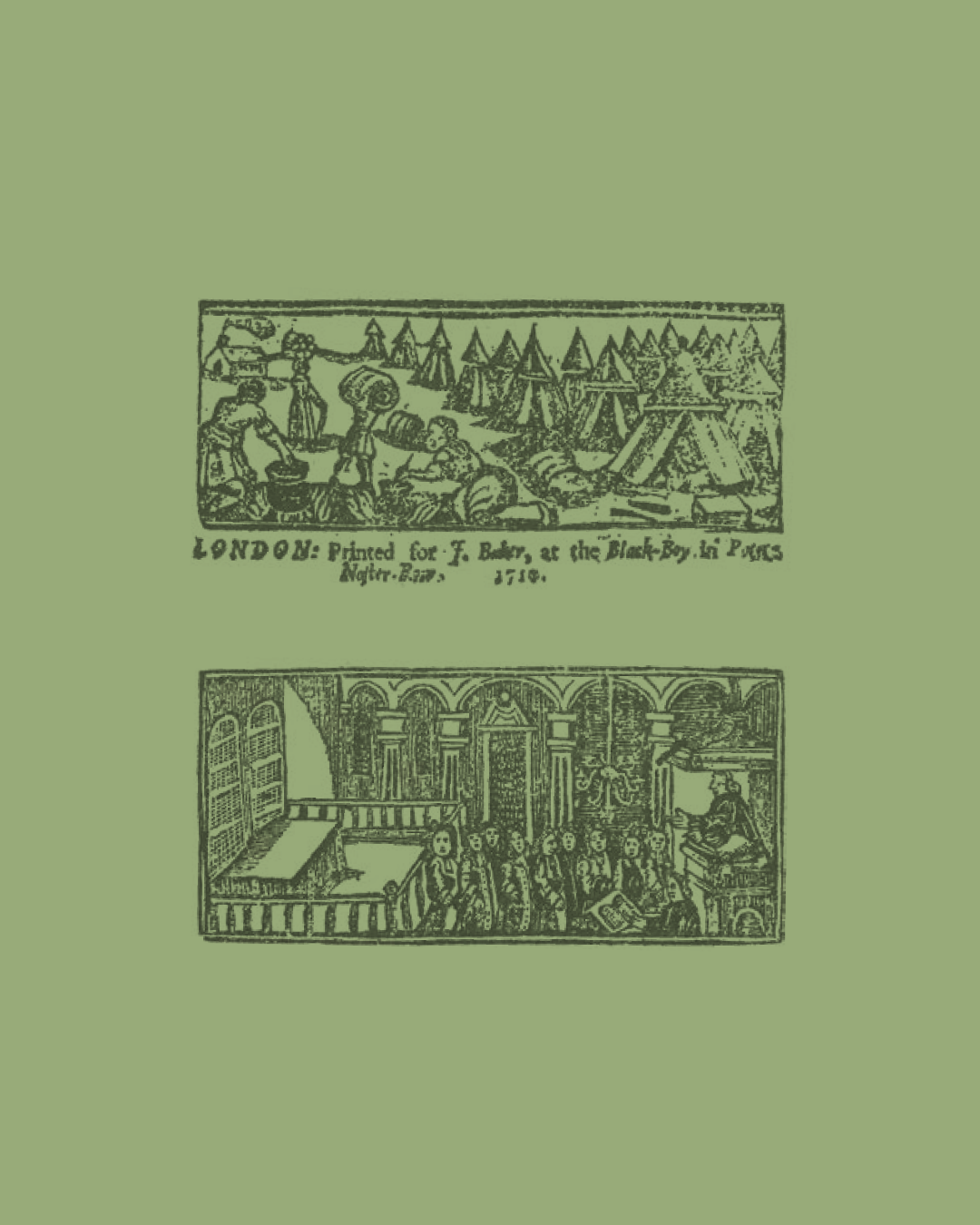

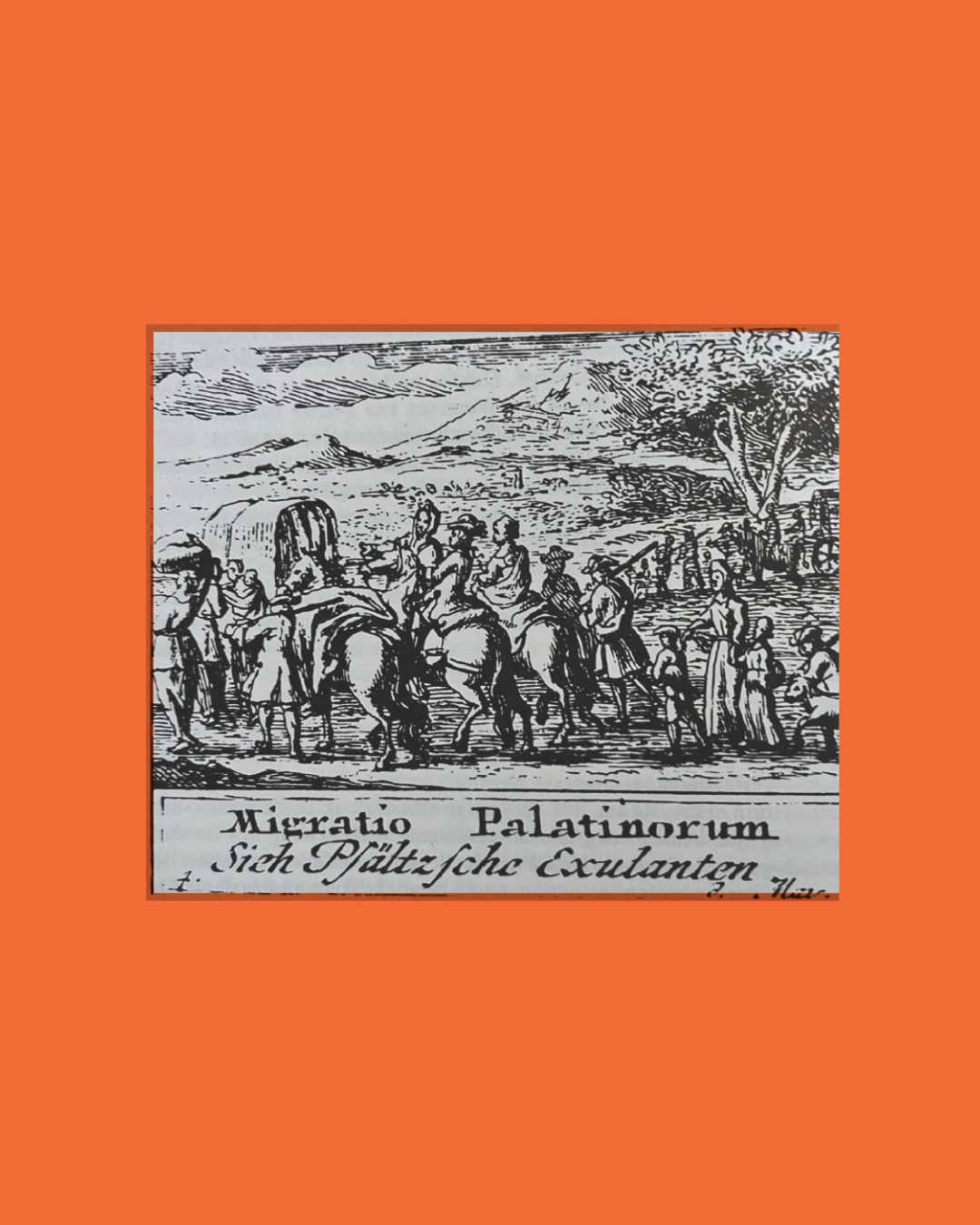

The arrival of the Palatines in Ireland was part of a much wider migratory trend, one of the largest and most significant in Early Modern Europe. Inspired by a group of over 50 Palatine refugees who reached Carolina via London the previous year with the English Crown’s support, 512 Palatines petitioned Queen Anne of Great Britain in May 1709.

Queen Anne responded positively to this petition from the largely Protestant Palatine population, although she expected modest numbers to arrive on English shores.

Instead of the 500 or so petitioners, some 13,000 refugees set sail along the River Rhine between May and October, before making the crossing on overcrowded ships from Rotterdam to London.

According to a source written 10 years after the exodus, over 8,500 were Palatines but many of the remainder came from other areas of contemporary Rhineland-Palatinate, as well as Hessen, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg.

Over 2,300 were from Darmstadt, for example, followed by 1,000 hailing from Hanau, 600 from Franconia, 500 from Speyer and Worms, 400 from Baden, 100 from Zweibrücken and 60 from Trier, amongst many others.

Queen Anne responded positively to this petition from the largely Protestant Palatine population, although she expected modest numbers to arrive on English shores.

Instead of the 500 or so petitioners, some 13,000 refugees set sail along the River Rhine between May and October, before making the crossing on overcrowded ships from Rotterdam to London.

According to a source written 10 years after the exodus, over 8,500 were Palatines but many of the remainder came from other areas of contemporary Rhineland-Palatinate, as well as Hessen, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg.

Over 2,300 were from Darmstadt, for example, followed by 1,000 hailing from Hanau, 600 from Franconia, 500 from Speyer and Worms, 400 from Baden, 100 from Zweibrücken and 60 from Trier, amongst many others.

Queen Anne’s initially warm reception soon cooled and by November 1709 Palatines were subject to deportation back to the Continent directly upon arrival, with notices to that effect circulated in Rotterdam.

Before this new policy could be implemented, however, a group of some 3,600 Palatines were supported in relocating to Ireland. Many from this cohort would become known as Irish Palatines.

The assistance they received was provided for by Protestant landlords in Ireland, wishing to increase their percentage of Protestant tenants, in line with the wider land transfers that had marked Irish history over the previous decades.

Queen Anne’s initially warm reception soon cooled and by November 1709 Palatines were subject to deportation back to the Continent directly upon arrival, with notices to that effect circulated in Rotterdam.

Before this new policy could be implemented, however, a group of some 3,600 Palatines were supported in relocating to Ireland. Many from this cohort would become known as Irish Palatines.

The assistance they received was provided for by Protestant landlords in Ireland, wishing to increase their percentage of Protestant tenants, in line with the wider land transfers that had marked Irish history over the previous decades.

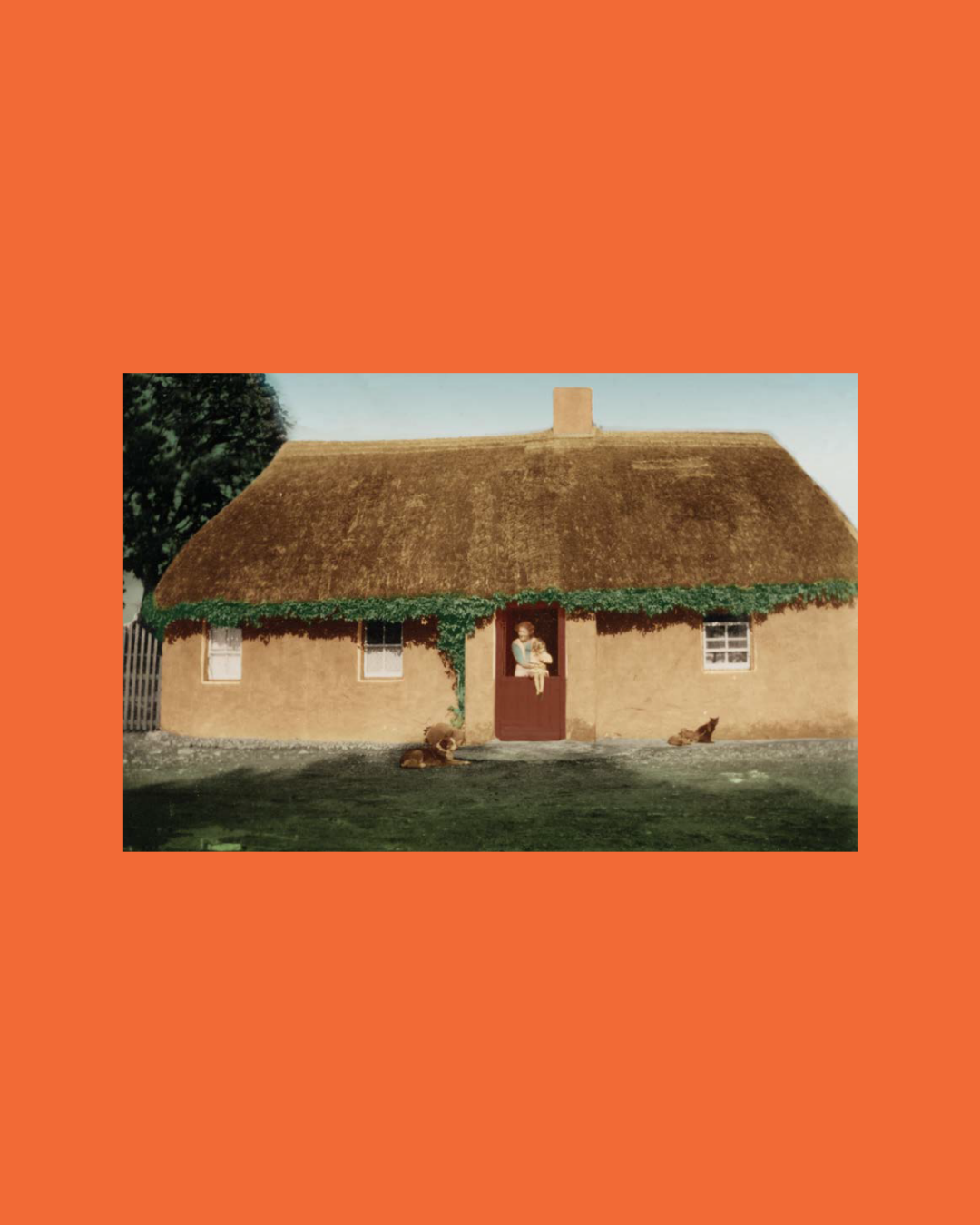

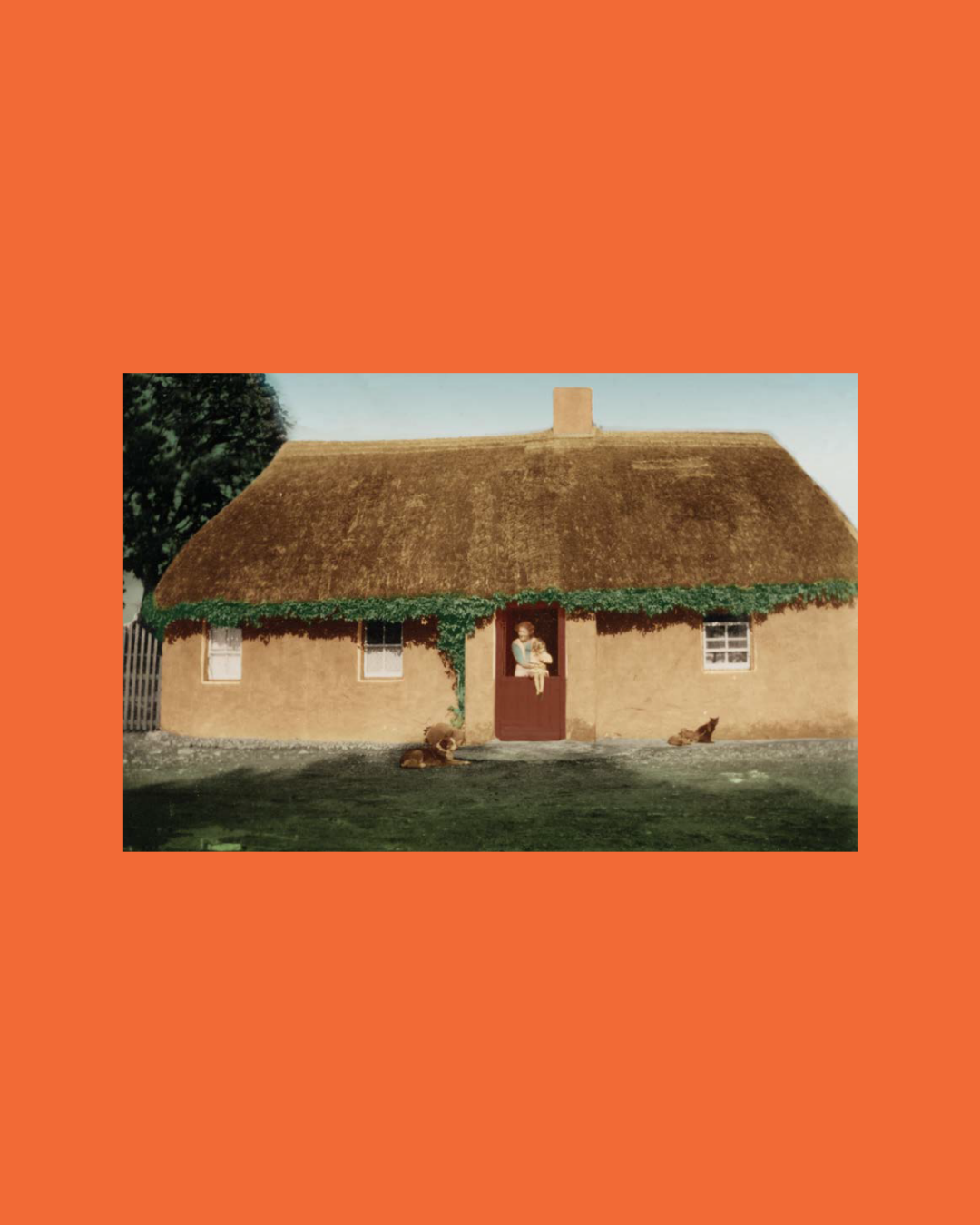

One landlord in particular, Thomas Southwell, 1st Baron Southwell of Castle Matrix near Rathkeale, Co. Limerick, was the most effective in attracting Palatine tenants.

Using a combination of government funding and his own personal fortune, some 130 families were settled on his lands by 1714. To this day, the areas around his historic demesne, places like Killeheen, Ballingrane, and Courtmatrix, have the largest concentrations of Irish Palatine descendants.

From Rathkeale, Irish Palatine settlements mushroomed nearby in Co. Limerick, Co. Tipperary and Co. Kerry.

A separate but not insignificant settlement was established in Co. Wexford by landlord, Abel Ram.

18th-century Irish Palatines married almost exclusively in their own circles, with only seven of 80 marriages recorded in Rathkeale between 1742 and 1780 with someone outside the Irish Palatine community.

498 children were born from these marriages, growing the Irish Palatine population in the area. As the lack of intermarriage suggests, the relationship between the Palatines and the local Irish population could be fraught, with tensions accentuated by the land transfers that had coloured previous decades.

18th-century Irish Palatines married almost exclusively in their own circles, with only seven of 80 marriages recorded in Rathkeale between 1742 and 1780 with someone outside the Irish Palatine community.

498 children were born from these marriages, growing the Irish Palatine population in the area. As the lack of intermarriage suggests, the relationship between the Palatines and the local Irish population could be fraught, with tensions accentuated by the land transfers that had coloured previous decades.

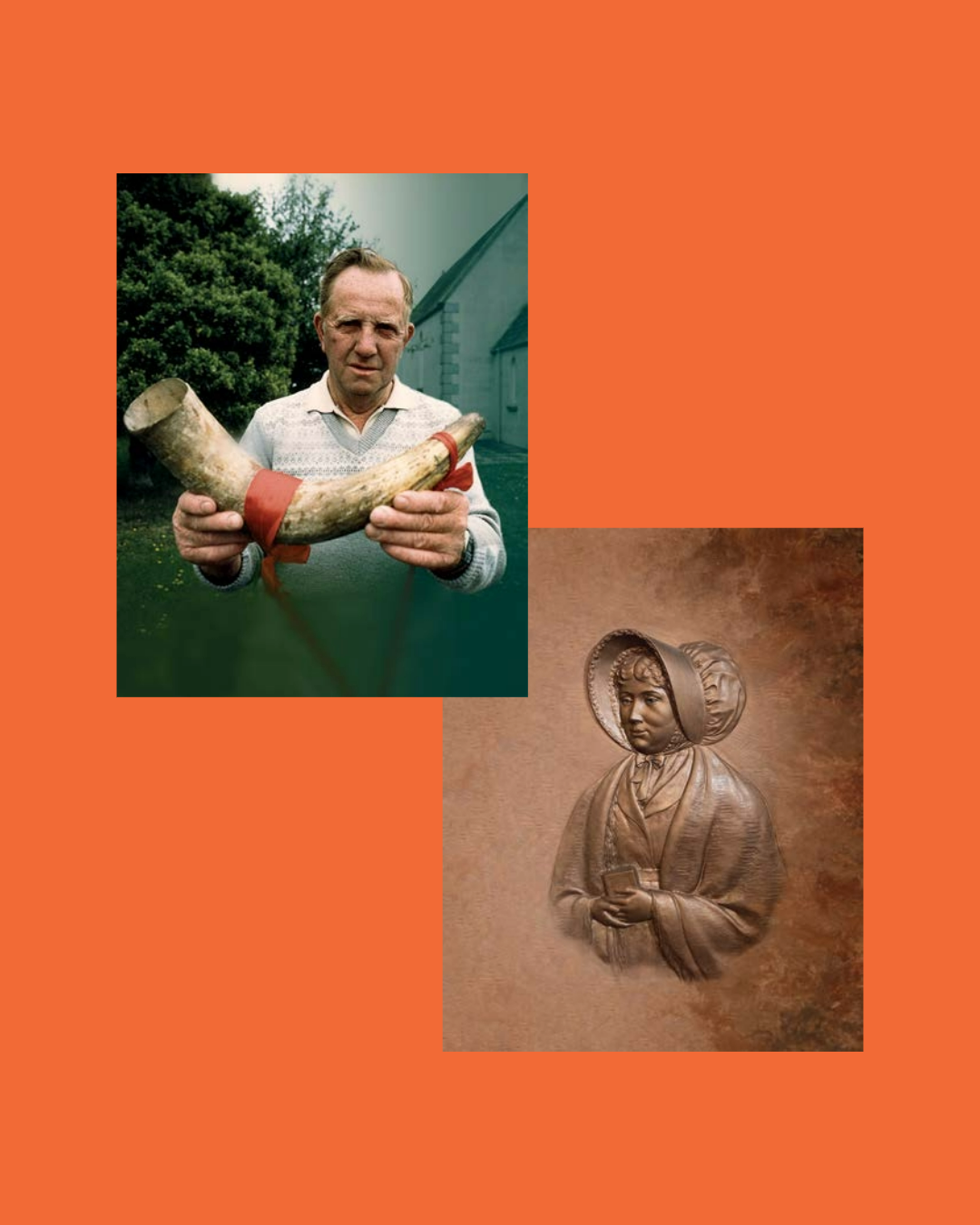

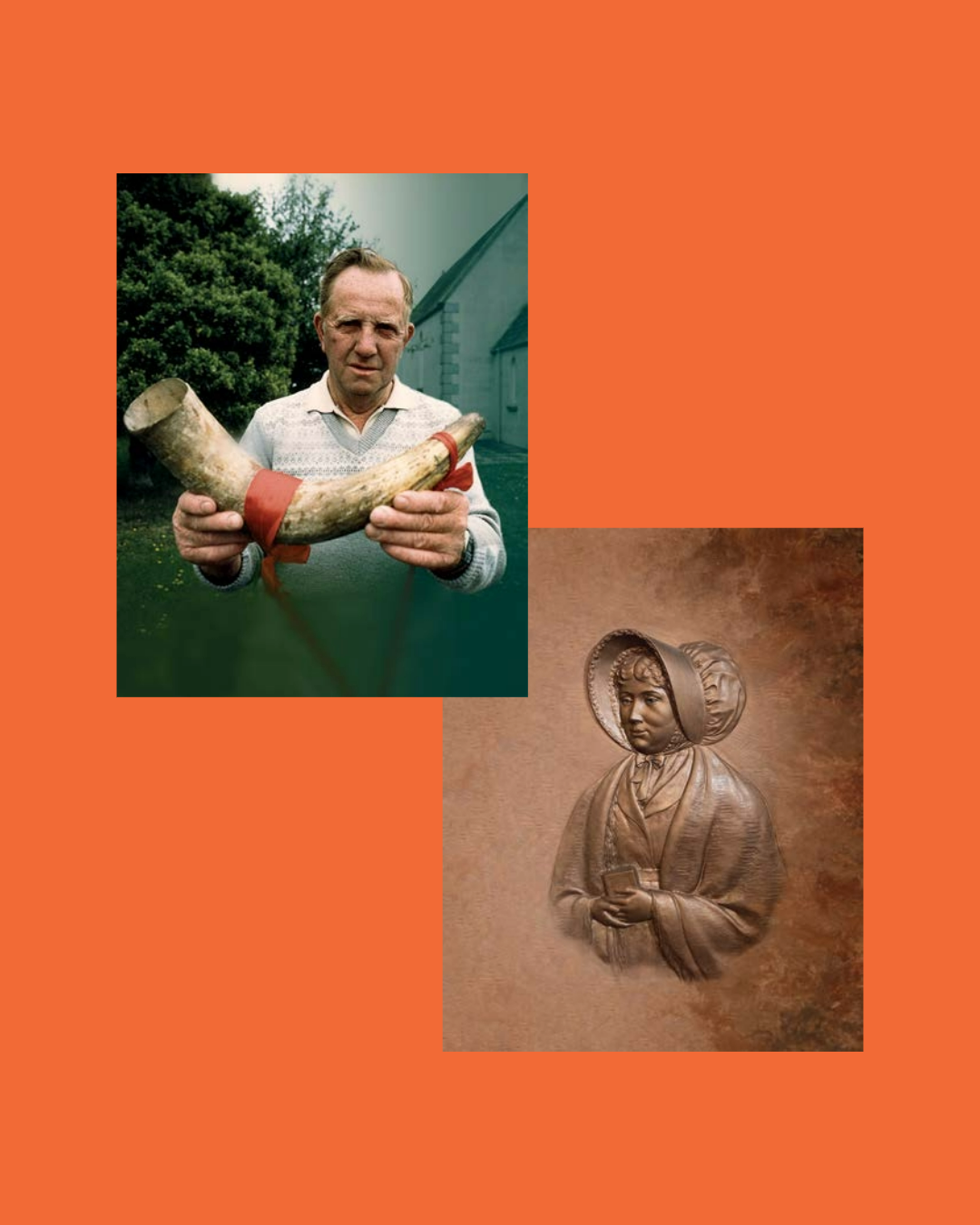

It may come as no surprise that many chose to leave this transient German bubble and Ireland altogether, with the stories of cousins Barbara Heck and Philip Embury underpinning just how transnational the early Irish Palatine experience was.

Born in Ballingrane, Co. Limerick, in 1734 and 1728 respectively, Heck and Embury were second generation Irish Palatines, with their parents having left Germany in the original 1709 wave.

They would go on to become hugely significant figures in the religious development of North America and were fondly remembered as the “Mother and Father of Methodism”.

It may come as no surprise that many chose to leave this transient German bubble and Ireland altogether, with the stories of cousins Barbara Heck and Philip Embury underpinning just how transnational the early Irish Palatine experience was.

Born in Ballingrane, Co. Limerick, in 1734 and 1728 respectively, Heck and Embury were second generation Irish Palatines, with their parents having left Germany in the original 1709 wave.

They would go on to become hugely significant figures in the religious development of North America and were fondly remembered as the “Mother and Father of Methodism”.

Irish Palatines that remained in Ireland had to contend with a deeply divided society, and the relatively peaceful island they arrived in would give way to unrest in the late 18th century, particularly after the ideals of the French Revolution spread to Irish shores.

Many Palatines would also comprise the ranks of the Limerick Militia, which was formed after 1793 in anticipation of a potential Irish rebellion.

Irish Palatines that remained in Ireland had to contend with a deeply divided society, and the relatively peaceful island they arrived in would give way to unrest in the late 18th century, particularly after the ideals of the French Revolution spread to Irish shores.

Many Palatines would also comprise the ranks of the Limerick Militia, which was formed after 1793 in anticipation of a potential Irish rebellion.

This rebellion came in 1798 and was led by Wolfe Tone and the Society of United Irishmen, a broad coalition originally formed by Belfast Presbyterians seeking to establish an Irish republic.

Given their alignment with non-revolutionary groups like the yeomanry and militia, Irish Palatines were targets of rebel activities, such as the Hornick family in Old Ross, Co. Wexford, where the fighting was especially intense. This pattern of hostility would continue after 1800, following the abolition of a devolved parliament in Dublin and the entry into force of a formal union between Ireland and Britain.

These years were characterised by agrarian agitation driven by secret societies like the Whiteboys and the Ribbonmen, who were opposed to landlord treatment of tenant farmers.

During the 19th century, we observe a pattern of Irish Palatines taking a more principled stance on the many social issues facing Ireland. Chief among them was the cause of Catholic emancipation championed by Daniel O’Connell in the late 1820s, with Irish Palatine names regularly appearing on petitions in favour of emancipation during that decade.

Irish Palatine and wider Protestant support no doubt contributed to the Irish-born British Prime Minister, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, passing the 1829 Emancipation Act through the Westminster Parliament. In doing so, Irish and British Roman Catholics could be admitted to Parliament, as well as to almost all public offices, in much the same way Irish Palatines could.

During the 19th century, we observe a pattern of Irish Palatines taking a more principled stance on the many social issues facing Ireland. Chief among them was the cause of Catholic emancipation championed by Daniel O’Connell in the late 1820s, with Irish Palatine names regularly appearing on petitions in favour of emancipation during that decade.

Irish Palatine and wider Protestant support no doubt contributed to the Irish-born British Prime Minister, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, passing the 1829 Emancipation Act through the Westminster Parliament. In doing so, Irish and British Roman Catholics could be admitted to Parliament, as well as to almost all public offices, in much the same way Irish Palatines could.

Similarly, in the aftermath of the Great Famine of 1845-52, during which over 1 million Irish people died and intercommunal relations were particularly strained, some Irish Palatines became Land League members.

Through this membership, they became party to the 1879 Land War and the cause of tenant ownership of the land they worked. One such Irish Palatine was Sylvester Poff from Ballymacelligott, Co. Kerry, who vigorously agitated for land reform.

Following Irish independence from Britain in 1922, the division between Irish Palatines and the rest of the Irish population became even less distinct.

Key in this regard was the passing of the Irish Free State Land Acts, which would eventually allow some 97.5% of Irish farmers to possess their land as freeholdings. This effectively dismantled the unrepresentative system of landownership that pervaded colonial Irish society.

Although they retained their distinct heritage and memory, Irish Palatines would fully integrate into life in independent Ireland, and in some cases become household names.

Following Irish independence from Britain in 1922, the division between Irish Palatines and the rest of the Irish population became even less distinct.

Key in this regard was the passing of the Irish Free State Land Acts, which would eventually allow some 97.5% of Irish farmers to possess their land as freeholdings. This effectively dismantled the unrepresentative system of landownership that pervaded colonial Irish society.

Although they retained their distinct heritage and memory, Irish Palatines would fully integrate into life in independent Ireland, and in some cases become household names.

Perhaps the best example of this is the Switzer family, whose chain of department stores in Dublin, Cork, Limerick and Galway, supplied luxury goods to the Irish public for over a century between 1838 and 1995. Today, the successor to Switzers, Brown Thomas, remains an institution in many of Ireland’s most well-known high streets.

Another Switzer would have similarly sizeable, albeit very different, impact on 20th century history. Mary Elizabeth Switzer was born in 1900 in Boston to an Irish Palatine family.

Mary Switzer played a leading role in the establishment of the World Health Organisation in 1948 and was Vice President of the World Relief Fund until her death in 1971. Throughout her lifetime, she maintained her connection to Ireland and was a frequent visitor to the island, underlining the complex geographic and interpersonal web that the Irish Palatine story represents.

Today, Austin Bovenizer and other Irish Palatine descendants like him are active in preserving and promoting this story, including by kindly contributing to the Irish Palatine Project.

Having studied at Limerick School of Art and Design, Austin most recently ran a successful graphic design business. He has long been aware of his Irish Palatine heritage, which led Austin to co-found the Irish Palatine Association in 1989.

From the Irish Palatine Heritage Centre in Rathkeale in Co. Limerick, the Association has members in Ireland, England, Australia, New Zealand, the USA, Canada and across the world, all connected by their identifying as or affinity for Irish Palatines and their history.

In Ireland, this cohort continues to be well represented across almost all sections of Irish society, and in some cases, have risen to the ranks of our most celebrated creatives.

From the Irish Palatine Heritage Centre in Rathkeale in Co. Limerick, the Association has members in Ireland, England, Australia, New Zealand, the USA, Canada and across the world, all connected by their identifying as or affinity for Irish Palatines and their history.

In Ireland, this cohort continues to be well represented across almost all sections of Irish society, and in some cases, have risen to the ranks of our most celebrated creatives.

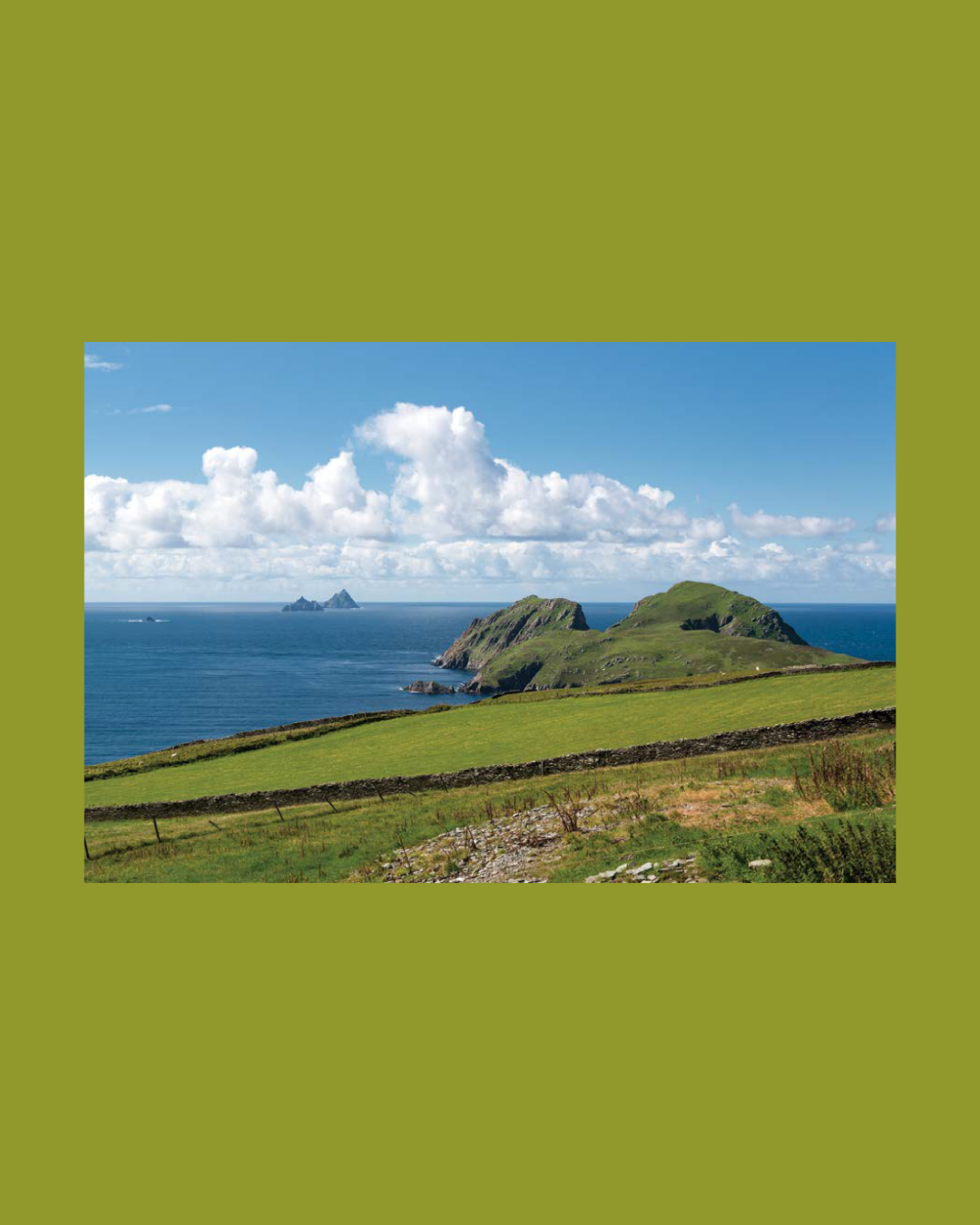

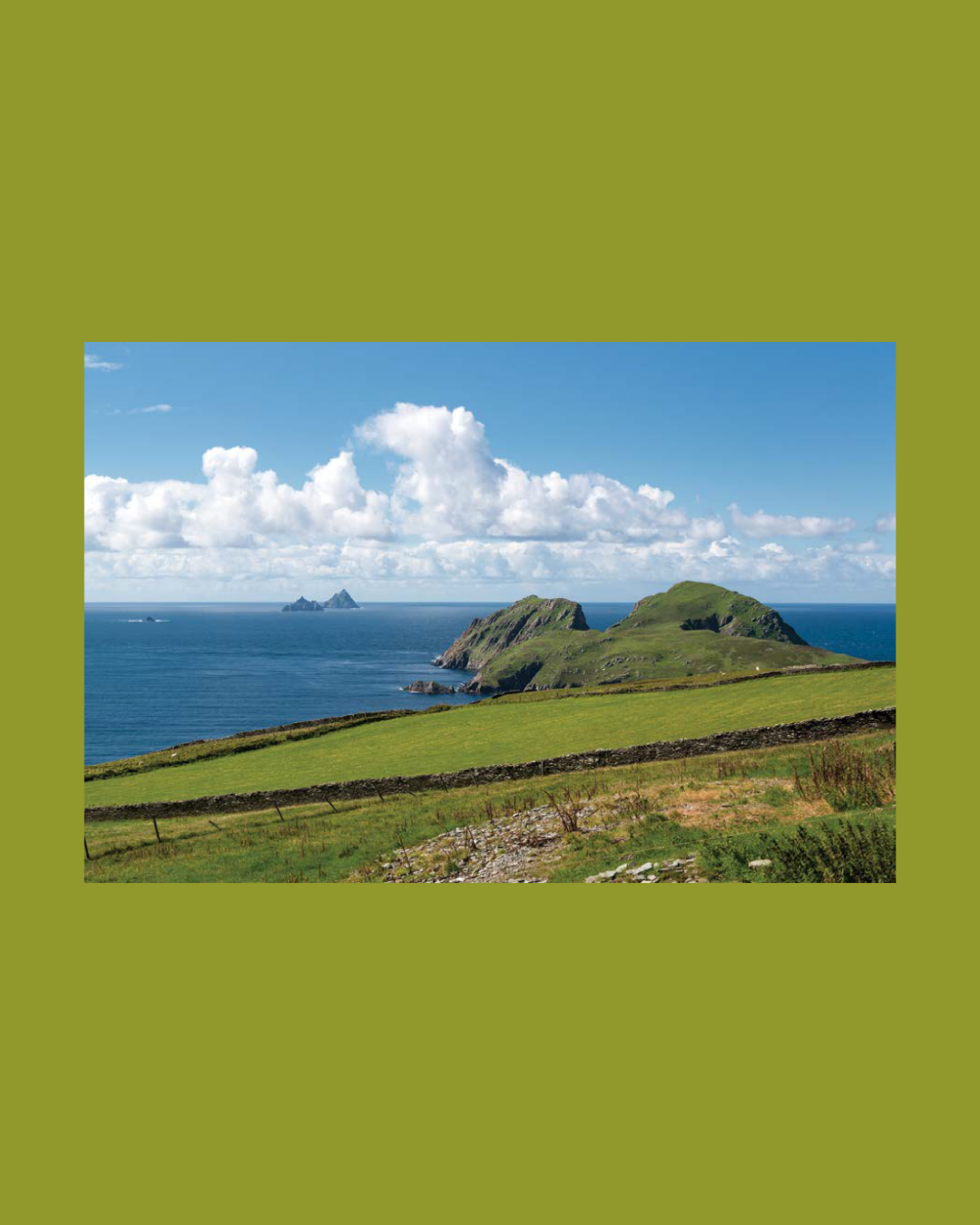

One such example is artist, Donald Teskey, who is a member of the Aosdána. Membership is awarded only to a small number of artists, whose work has made an outstanding contribution to the arts in Ireland. He is famous for his landscapes that focus on the ruggedness of Ireland’s western seaboard, articulating the relentless, energetic and elemental forces of nature on the Atlantic coastline.

Discover more of the Irish Palatines story

We hope you have found this unique strand of Irish-German history as compelling as we have.

We invite you all to engage further with this story and indeed, with the wider relationship between our two countries that continues to add so much value at that fundamental, human level.

Credits

The Consulate General of Ireland, Frankfurt commissioned this booklet and exhibition with thanks to:

Alexandra Bogensperger, Austin Bovenizer, Jim Culleton, Pamela Fischer, Dr. Gisela Holfter, Deirdre Kinahan, Dr. Sabine Klapp, Dr. Maximilian Lässig, Barbara Schmidt, Julia van Duijvenvoorde, Jörg Vorhaben, Fishamble: The New Play Company, Heidelberg University, the Institute for Palatine History and Folklife Studies, the Irish Palatines Association, the Irish Palatines Centre, the State Theatre Mainz, the State Government of Rhineland Palatinate, Tourism Ireland; the University of Limerick and designer, Una Helbig.

The views expressed in both are those of the author and not of the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade or its missions abroad.