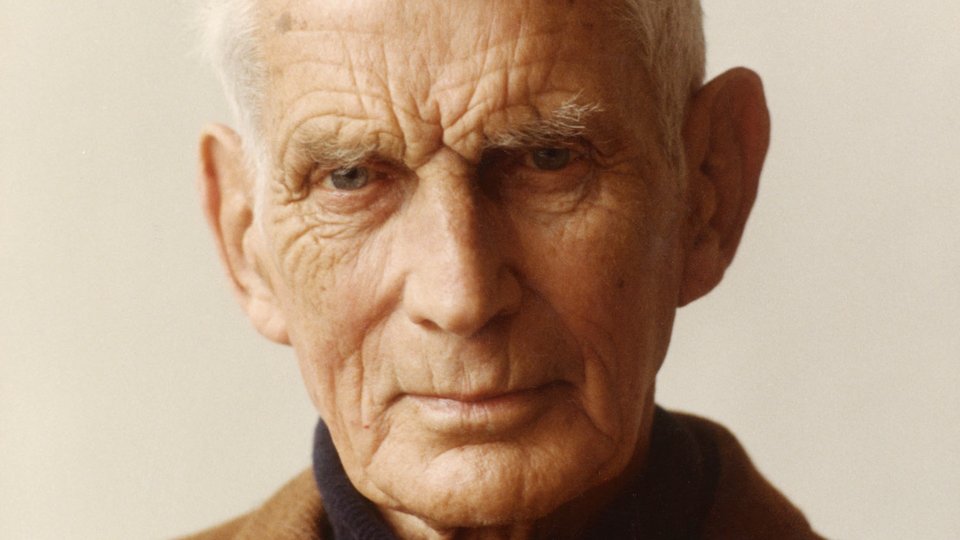

Samuel Beckett in Germany: A creative bond across borders

The invisible string that tied Samuel Beckett to Germany was long, complex and deeply personal. Over the course of his life, Beckett maintained a strong and evolving relationship with German culture, one shaped by his love of literature, art and music, as well as by the friendships and experiences he gathered on his travels through the country.

To explore this unique and sometimes overlooked connection, Professor of Modern Literature and Beckett Studies at the University of Reading, Mark Nixon, takes us on a journey through Beckett’s time in Germany. In this rich and detailed account, we see how Beckett’s encounters with German people, places and ideas left a lasting mark on his life and work, and how, in turn, Beckett influenced German theatre, media and artistic thought.

Read Professor Nixon’s essay below:

Beckett in Germany

In his 1954 homage to the Irish painter Jack B. Yeats, Samuel Beckett stated that ‘The artist who stakes his being is from nowhere, has no kith’. Beckett himself is often seen as an artist untethered from, and unencumbered by, national cultural discourses, confronting instead the more universal question of what it means to be human.

His work – for stage, television and radio, as well as his prose and poetry – continues to be discovered across the world, by new generations of theatregoers and readers. The strangely compelling force of his texts continues to provoke artists working in a wide array of cultural fields to respond to them in unique ways in productions, adaptations and artistic reverberations.

Cultural lineages through Europe

Born in Ireland in 1906, educated in and travelling through the grand traditions of European literature and culture, settling in Paris, writing in both English and French, and working also in German and Italian, Beckett both in form and content persistently stays a step ahead of any attempts at assimilation or categorisation.

Yet it is possible to discern particularly productive cultural lineages, points of reference that Beckett absorbed and revisited across his long writing career. Already in the early 1930s Beckett professed to suffer from a ‘German fever’, which had as much to do with personal affiliations as with a relationship with German culture that would significantly shape his creative and aesthetic output over the next five decades.

Beckett’s introduction to Germany

On a personal level, Beckett’s introduction to Germany occurred during his visits to his relatives, the Sinclairs, in the years 1928-32, who lived in Kassel. His love affair with Peggy Sinclair, and the liberal attitudes of her parents, Cissie and William ‘Boss’ Sinclair, undoubtedly laid the foundation of a deep engagement with the country.

Indeed, throughout the 1930s, German culture profoundly influenced Beckett’s thinking and writing as he absorbed the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, the music of Franz Schubert and the work of various authors, in particular Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Deep German studies

Beckett’s surviving notes on German literary history, as well as his vocabulary notebooks, reveal his assiduous study of all things German in the mid-1930s, which was complemented by his reading, in German, of Goethe, Schiller, Grillparzer, Hölderlin and Rilke.

Just how important German had become for Beckett by 1936 is illustrated by the fact that his very first attempt at writing a dramatic piece, long before the success of En attendant Godot (written in French), was a theatrical pastiche of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso written in German, entitled ‘Mittelalterliches Dreieck’ (‘Medieval Triangle’).

Winterreise in Germany

A love of German culture is one thing, a trip to Nazi Germany is another thing. We will never really know what persuaded Beckett to embark on a six-month journey through Germany between October 1936 and March 1937. His ‘German Diaries’, the only diary Beckett is known to have kept, reveal that he wished to improve his German language skills and to study the paintings in German art galleries before they became inaccessible.

Indeed, as he arrived in Hamburg in October 1936, the Nazi regime began to remove paintings from galleries, and to repress more forcefully any cultural expression, in whatever form, they deemed ‘degenerate’. It is difficult to overestimate the importance that this ‘Winterreise’ had on Beckett’s development as an artist, not only in terms of his aesthetics, but also quite simply in terms of what it meant to be an artist.

‘Literature of the unword’

We have a letter that Beckett wrote in July 1937 to an acquaintance he made in Germany, the young bookseller Axel Kaun, after his return to Ireland, which gives voice to this fundamental shift in outlook.

Written in German, Beckett bemoans the fact that the English language, its grammar and style, has become as ‘irrelevant as a Victorian bathing suit’, and argues that ‘language is most efficiently used where it is being most efficiently misused’. What he advocates is a ‘literature of the unword’ (‘eine Literatur des Unworts’), which epitomises, in many ways, the texts that Beckett will proceed to write in different media and what we now think of as the ‘Beckettian’.

A return to Germany

When Beckett returned to Germany, 20 years after the end of the Second World War, he was a different, and now truly bilingual, writer. With the trilogy of novels Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnamable, the two plays Waiting for Godot and Endgame, as well as a range of other writings in both French and English, Beckett had rewritten and reimaged both the stage and the page.

Schiller Theater years

Yet it was in Germany, at the Schiller Theater in Berlin, that Beckett also became a formidable theatre director, directing seven of his theatrical plays between 1967 and 1978 in productions that are often seen as embodying most closely his dramatic vision.

His theatrical notebooks, which record his meticulous preparations for these stagings, are now preserved in the archive of the Beckett International Foundation at the University of Reading.

‘Crazy inventions for TV’

At the same time, Beckett found a productive working environment at the studios of the Süddeutscher Rundfunk in Stuttgart, which allowed him to realise what he would later call his ‘crazy inventions for TV’. Here, between 1965 and 1985, he directed and recorded the definite versions of his television plays in an atmosphere of conducive collaboration.

Everlasting German inspirations

Beckett continued to draw on his love of German literature until the very end of his long writing career, as he continued to invoke and read the writers he had encountered in the 1930s. In Beckett’s penultimate text, the short story Stirrings Still published a year before his death in 1989, for example, the figure of the German 13th century Minnesänger Walther von der Vogelweide is seen sitting on a stone, evoking the poem ‘ich saz ûf eime steine’.

A lasting legacy

Beckett’s work circles around impotence, failure and liminality with an unflinching commitment to articulating the raw experience of the human condition. His texts continue to resonate in times of social, economic, ecological and political uncertainty; they speak to us in these challenging times precisely because they refuse to offer facile solutions.

Yet if Beckett’s work is often bleak, it is also infused with humour, solidarity and empathy, offering glimpses of the way we might envisage a fairer society. If Beckett set out to tackle the impossible task of finding a form that ‘accommodates the mess’, as he said, then Germany and German culture played a pivotal role in that journey.

Meet the author

Mark Nixon is Professor of Modern Literature and Beckett Studies at the University of Reading, where he is also Co-Director of the Beckett International Foundation. With Dirk Van Hulle, he is editor-in-chief of the Journal of Beckett Studies, Co-Director of the Beckett Digital Manuscript Project and series editor of ‘Elements in Beckett Studies’.

Nixon has authored or edited more than twenty books on Beckett’s work, and is currently preparing a critical edition of Beckett’s ‘German Diaries’ (with Oliver Lubrich; Suhrkamp, 2026). He also edited, along with Dirk Van Hulle, a catalogue of an exhibition the Literaturmuseum der Moderne in Marbach in 2017-2018.

Mark Nixon spoke at ‘Beckett in Babylon’ , an unprecedented three-day programme that shone a light on Samuel Beckett’s work in Germany, which toke place at the historic Babylon Kino in Berlin, and was presented by The Embassy of Ireland.